As always, if you are impatient for one of these updates, the 2020 pages on Election Graphs are updated every day as new polls come in. Or you can follow @ElecCollPolls on Twitter to see all the polls as I add them.

The last blog update here was 10 days ago on October 10th. Here are the high-level changes since that last post:

| Model | Metric | 10 Oct | 20 Oct | 𝚫 |

| Probabilities (Indep States) |

Trump 2σ Median Biden 2σ |

Biden +78 Biden +174 Biden +276 |

Biden +32 Biden +140 Biden +254 |

Trump +42 Trump +34 Trump +22 |

| Trump Win Tie Biden Win |

0.0% 0.0% 100.0% |

0.3% 0.0% 99.7% |

+0.3% FLAT -0.3% |

|

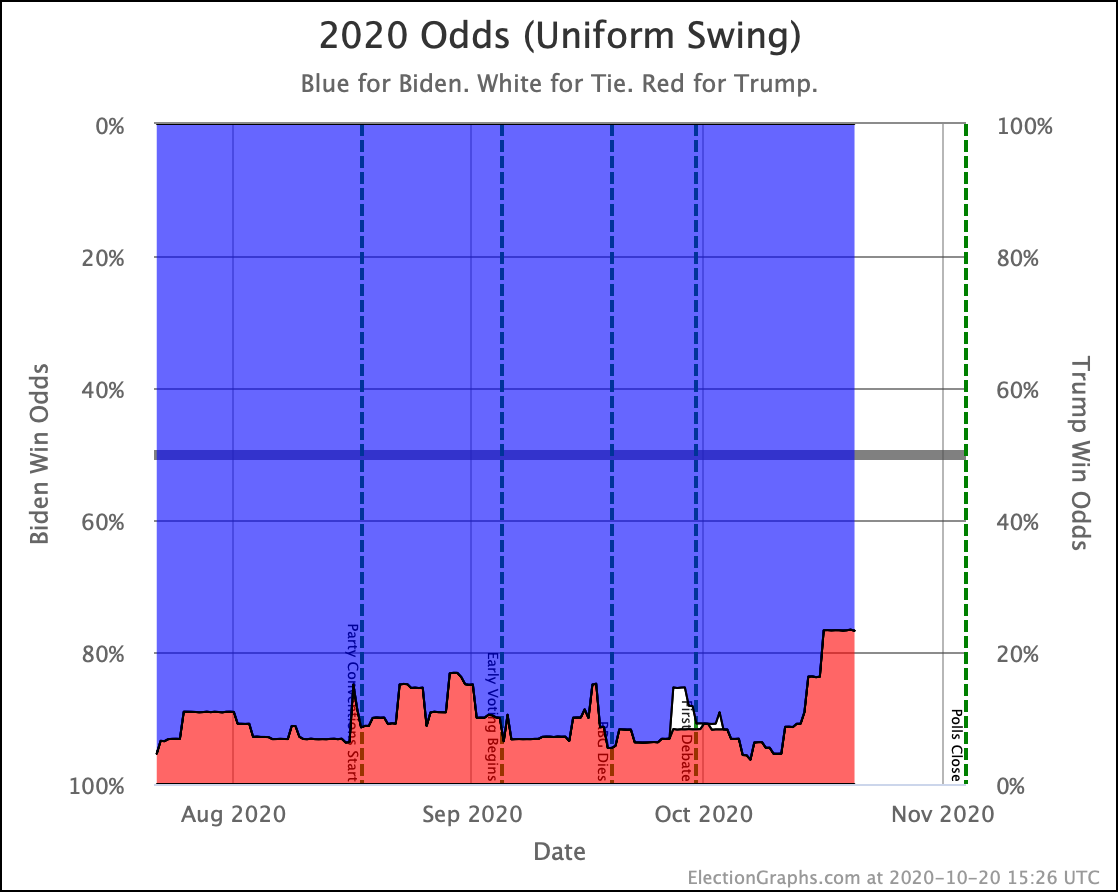

| Probabilities (Uniform Swing) |

Trump 2σ Median Biden 2σ |

Trump +12 Biden +176 Biden +326 |

Trump +52 Biden +164 Biden +294 |

Trump +40 Trump +12 Trump +32 |

| Trump Win Tie Biden Win |

5.2% 0.0% 94.8% |

23.3% 0.0% 76.7% |

+18.1% FLAT -18.1% |

|

| Categories | Trump Best Expected Biden Best |

Biden +20 Biden +212 Biden +288 |

Trump +40 Biden +164 Biden +294 |

Trump +60 Trump +48 Biden +6 |

| Tipping Point | Biden +6.2% | Biden +3.1% | Trump +3.1% |

We'll hit the main story for this update before going through the cavalcade of all of the charts:

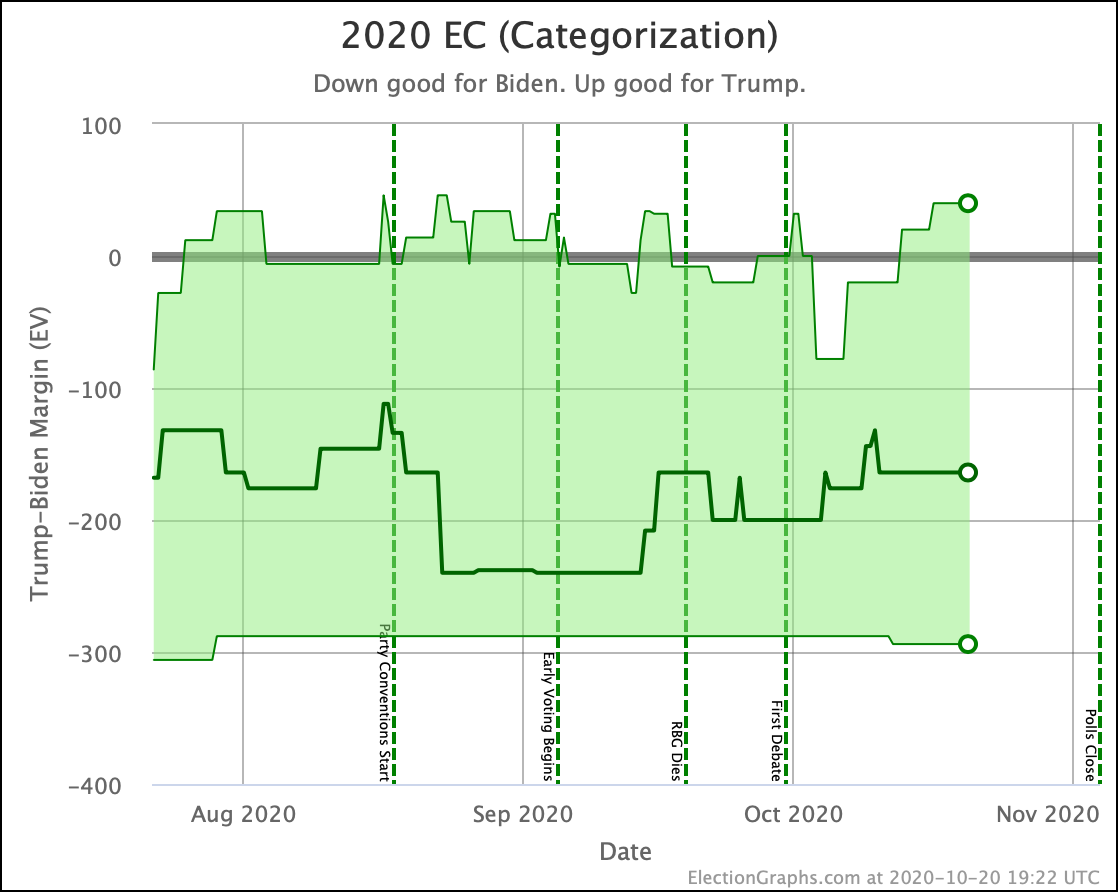

Last time we said "not too fast" to notions that Trump's numbers were collapsing. Instead, we suggested that Trump was just at the low end of the normal range we had been in since June, and it would be unsurprising to see some reversion to the mean.

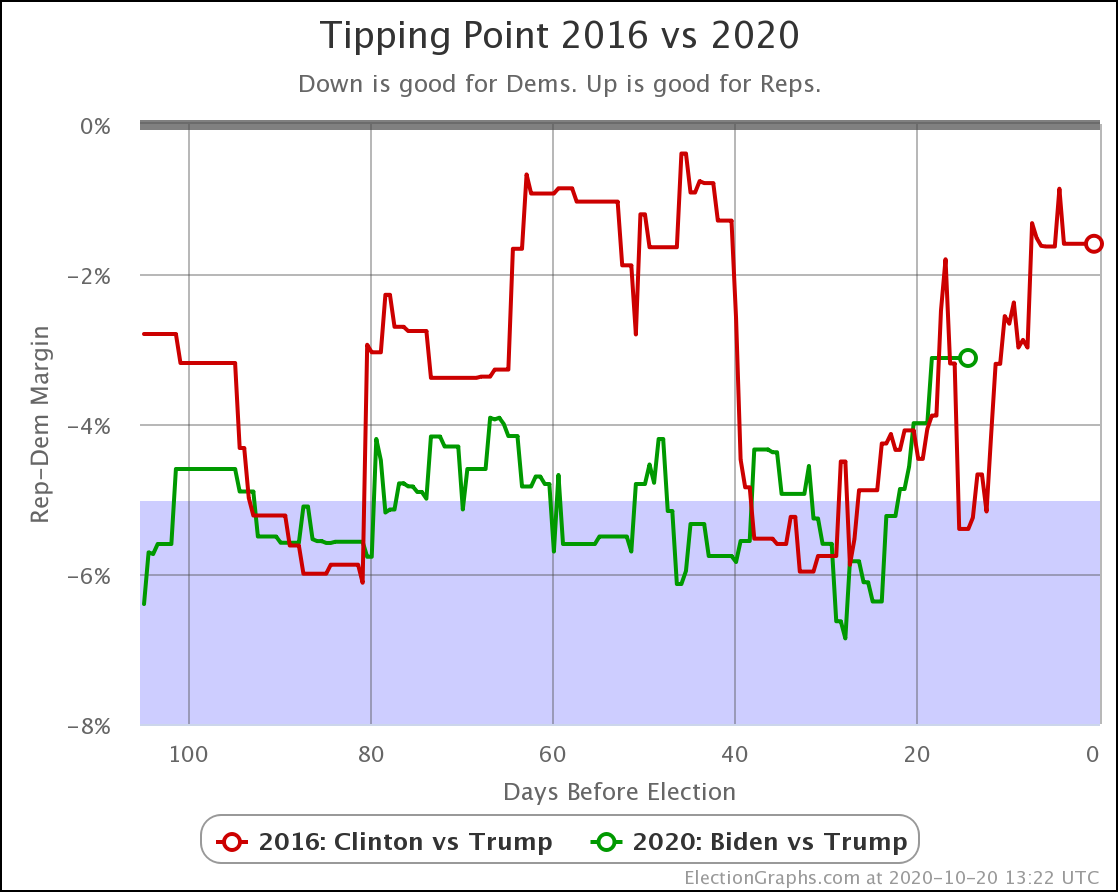

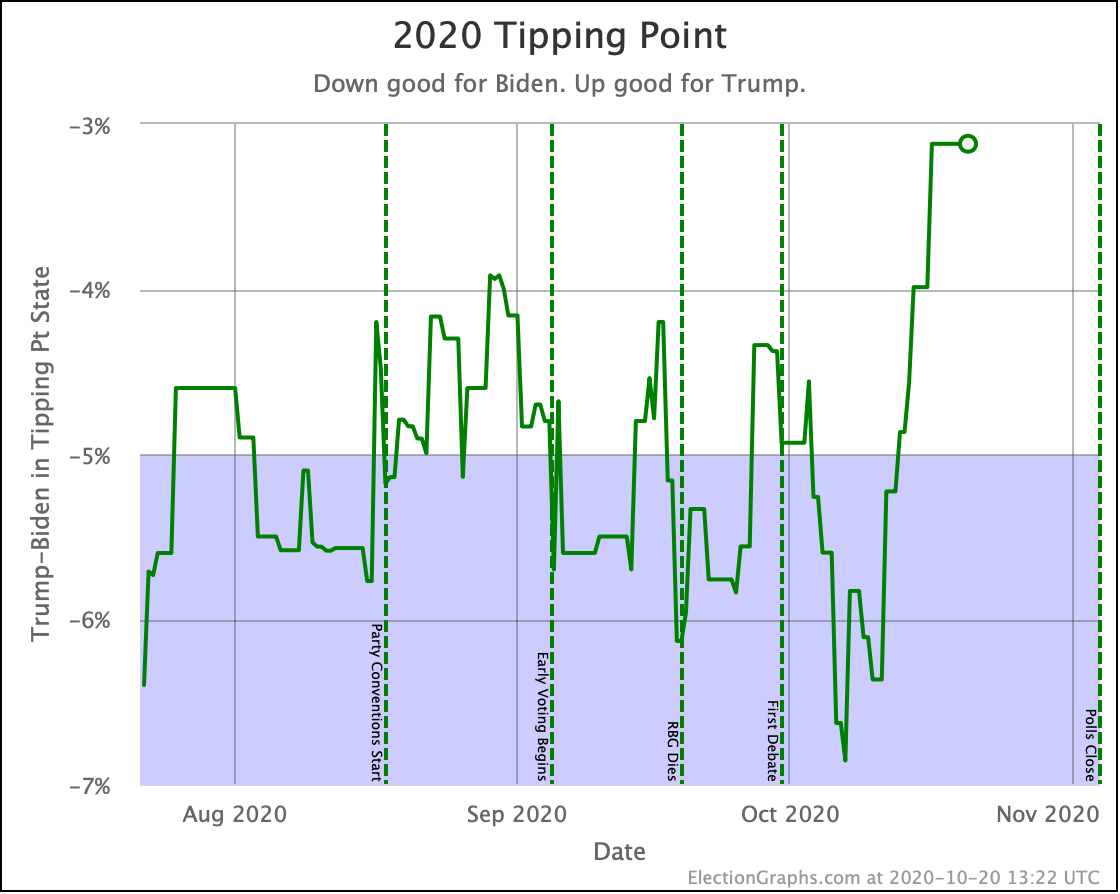

And that is exactly what we have seen. Things have moved back toward Trump on almost all metrics we track. In fact, in the critical tipping point metric, we've moved out of the 4% to 6% Biden lead band that we have been in since June, as Biden falls to 3.1%.

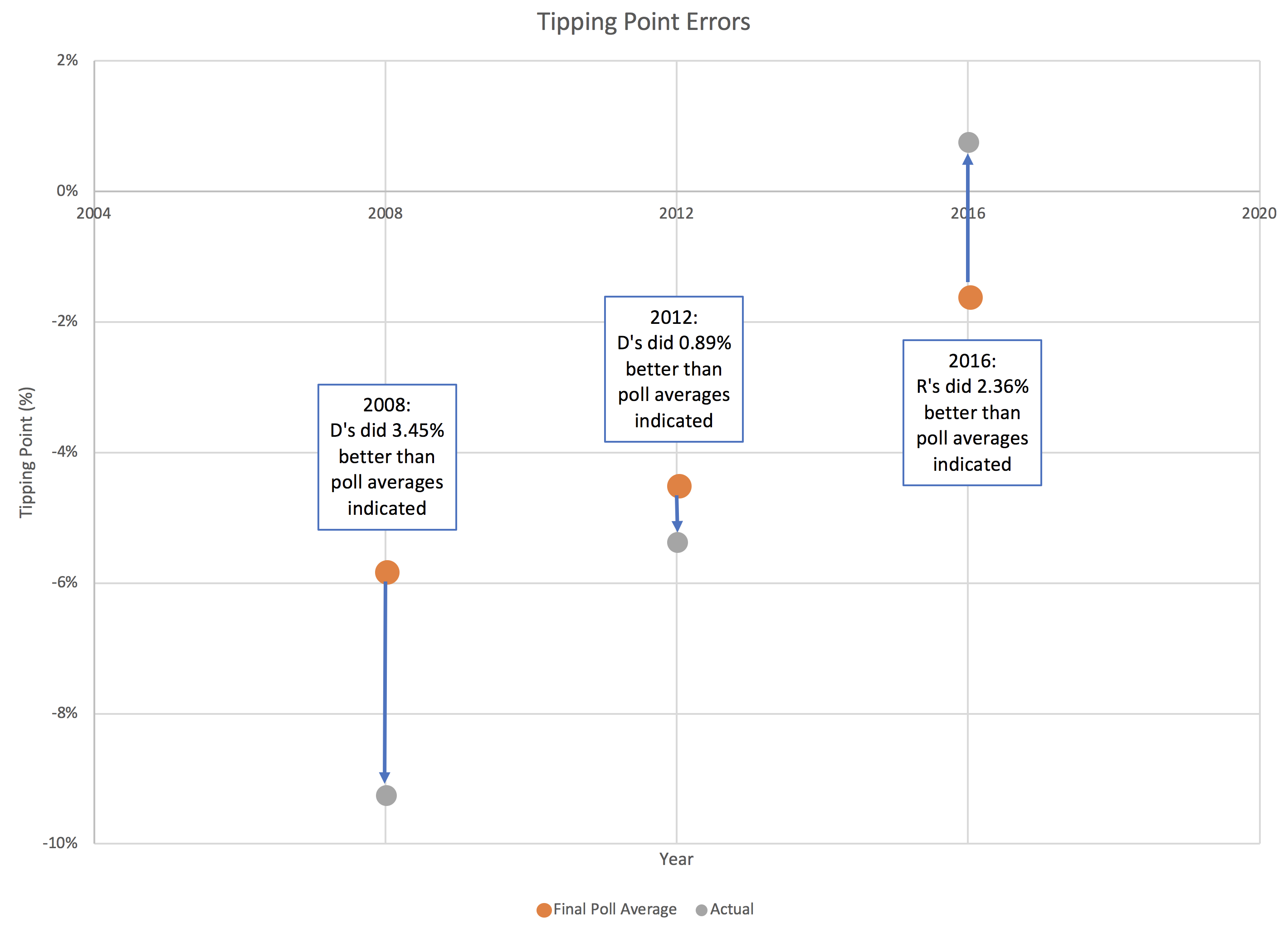

In the three election cycles we have tracked this, the largest difference between the final tipping point and the actual tipping point in the election was not in 2016. It was in 2008. Nobody cared, because the actual results were a bigger Obama win than predicted by the polls, rather than having a different winner than the polls predicted. But in 2008 the final tipping point was off by 3.45%. That is a bigger error than the 3.1% that currently separates Biden's tipping point from a Trump win.

So we are in the zone where simple polling error could make the difference to who is leading, even without further "movement".

As a consequence, the chances of a Trump win in the Uniform Swing view (the most optimistic for him) have jumped up to 23.3%.

Wow. This is a big change.

Reader Jonathan T emailed to ask if I had any thoughts on the possible causes of this big change. So let's talk about that.

Rather than look for a specific "cause" though, it is worth discussing if this change is even "real".

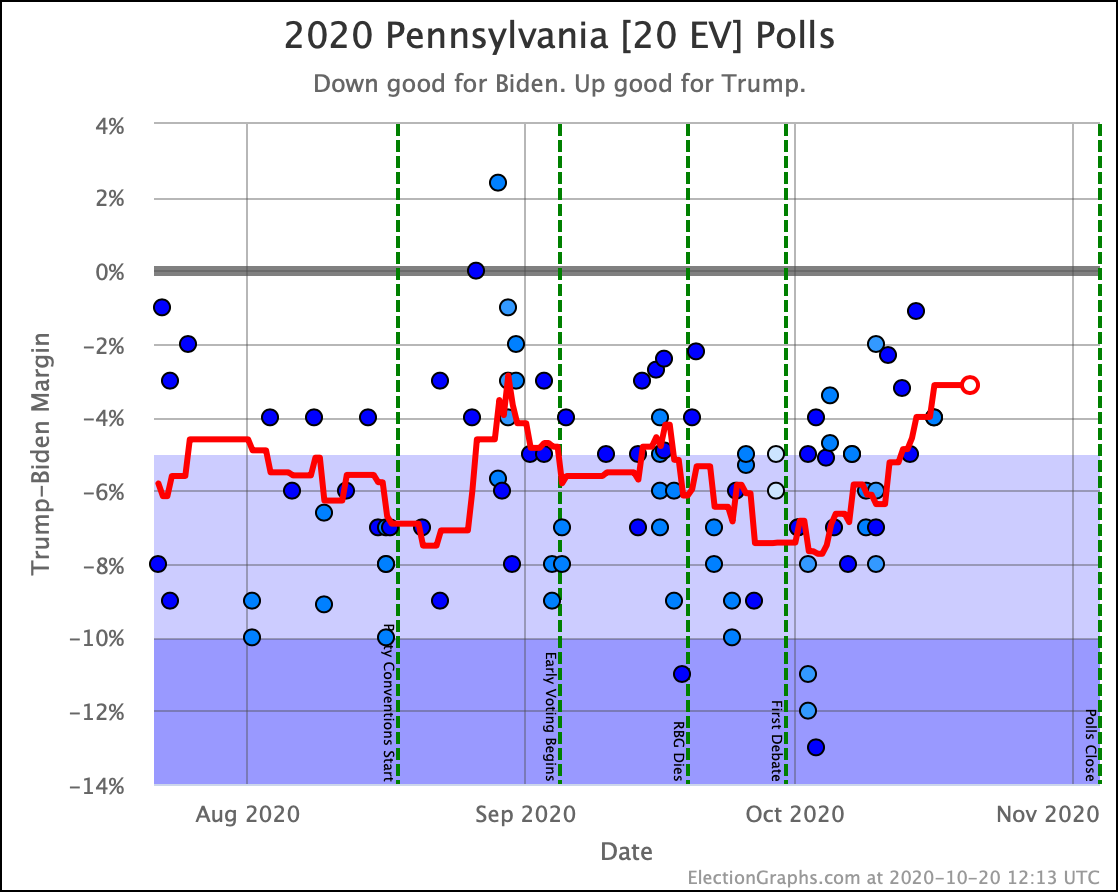

The tipping point change is driven by one state. Pennsylvania.

As polls that were very favorable to Biden from early October drop off the average, they are being replaced by new polls that show a much narrower race.

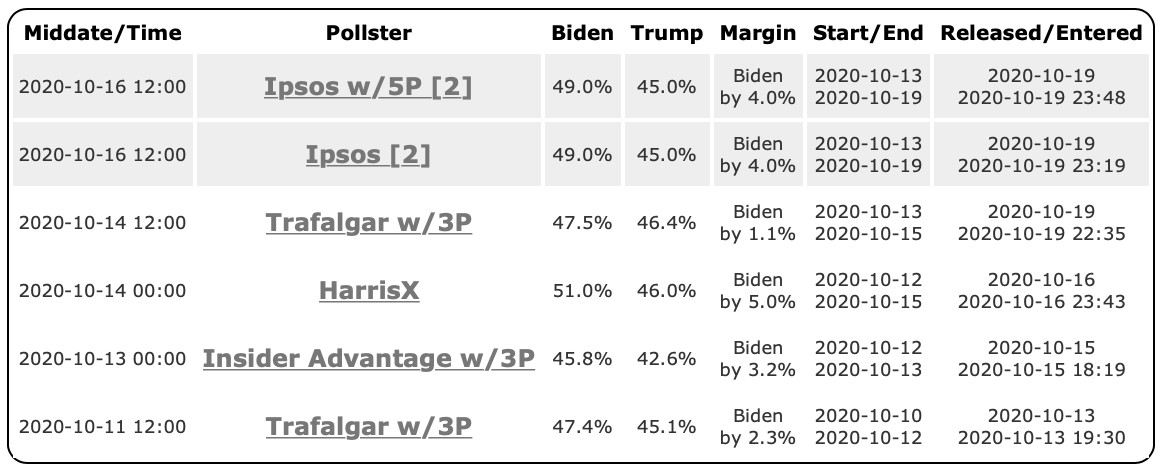

Now, what are the actual polls currently in my Pennsylvania average?

Why do I bring up the specific pollsters? I never bring up the specific pollsters. I just throw them into the average.

Well, I bring it up because right now we have no big-name high-quality pollsters in the mix. In fact, we have Trafalgar, which is widely panned as intentionally constructing their polls to find "hidden" conservative voters, and therefore push results to the right, show up twice! And we have others that people have criticized as being lower quality for one reason or another.

538's Nate Silver tweeted this earlier today:

Folks, Biden's lead didn't shrink from 7.3 points to 3.6 points in PA in a week (as per RCP) at the same time it was steady or slightly growing nationally. This is why you need poll averages that take a longer time horizon and/or adjust for house effects.

RCP's averages are extremely subject to who happens to have polled the state recently, which is often the spammier, lower-quality pollsters, and that's been especially true recently with live-caller polls not having been terribly active in the states over the past 2 weeks.

I love many things about RCP, but if you have an average and 1/3 of it consists of Trafalgar and InsiderAdvantage and 0% of it consists of live-caller polls, it's not going to be a very reliable average.

He is talking about the RCP Pennsylvania average, not Election Graphs. We're too small for 538 to notice. But all of the same things are true for us.

Both Election Graphs and RCP are straight numerical averages without weighting for historical pollster quality or correcting for historical pollster bias. And we both decide which polls to include in ways that result in looking at narrower time windows as the election approaches.

These are valid criticisms. This may be a temporary transient spike caused by a series of polls from low-quality pollsters which will immediately move back in the other direction as soon as the bigger more respected pollsters put out some new numbers.

If I had to bet right now, I'd actually bet on that. We moved from the high end of Biden's range in PA to the low end of his range, and I would expect to see it revert back to the middle since we have been in a pretty steady range for months, and this seems to be an aberration, especially since there are no big news events, and as Nate Silver points out, we haven't seen a similar movement in the national polls.

But…

Let's do a quick look at where a bunch of websites ended up right before Election Day in 2016. This is from a post-mortem I did of the 2016 performance of Election Graphs. At the time I logged the following as the final electoral college predictions from a bunch of sites:

- Clinton 323 Trump 215 (108 EV Clinton margin) – Daily Kos

- Clinton 323 Trump 215 (108 EV Clinton margin) – Huffington Post

- Clinton 323 Trump 215 (108 EV Clinton margin) – Roth

- Clinton 323 Trump 215 (108 EV Clinton margin) – PollyVote

- Clinton 322 Trump 216 (106 EV Clinton margin) – New York Times

- Clinton 322 Trump 216 (106 EV Clinton margin) – Sabato

- Clinton 307 Trump 231 (76 EV Clinton margin) – Princeton Election Consortium

- Clinton 306 Trump 232 (74 EV Clinton margin) – Election Betting Odds

- Clinton 302 Trump 235 (67 EV Clinton margin) – FiveThirtyEight

- Clinton 276 Trump 262 (14 EV Clinton margin) – HorsesAss

- Clinton 273 Trump 265 (8 EV Clinton margin) – Election Graphs

- Clinton 272 Trump 266 (6 EV Clinton margin) – Real Clear Politics

- Clinton 232 Trump 306 (74 EV Trump margin) – Actual "earned" result

Hmmm. Who got closest to the actual results? Election Graphs and RCP.

And specifically, WHY did that happen? My hypotheses are:

- We both were averaging based on very short time frames by the time we got to the election, allowing us to catch a last-minute move that was "smoothed out" from a lot of the other sites.

- We both included some of these low-quality pollsters, including Trafalgar, who started to show movement toward Trump that the other pollsters were not showing.

I could be wrong, I have not done an in depth analysis, but at first blush, those seem to be the common elements.

Now, as I said, I would still bet on reversion to the mean here, and that we will see Pennsylvania bounce back toward a greater than 5% Biden lead over the next week or so as new polls come in.

But in 2016, right before the end, I doubted the results of my own average because it was moving in a way that most of the big sites were not in that last week and because there were other sites specifically calling out Trafalgar and others as garbage noise that maybe should just be excluded from the averages because they were clearly biased and wrong. But it turned out those polls were closer to what actually happened than some of the others.

So we're not doing that this time. We throw in all the polls, and we see what happens, and yes, near the election we have a very short time frame, so what polls have been in the field lately does make a big difference. But we are where we are.

At the moment Election Graphs shows a significant tightening in Pennsylvania. And because Pennsylvania is the tipping-point state, and there is somewhat of a gap between the states that are closer than Pennsylvania and the states where Biden has a more solid lead, that means that as Pennsylvania moves, so does the national race, at least for the moment.

Don't be surprised if this moves back in the opposite direction tomorrow though. And don't be surprised if the high-quality polls confirm this movement and it stays tight either. I view that as less likely, but certainly not impossible. I'm not going to preemptively say to ignore this tightening as clearly not real though. In 2016, it was an indicator of actual tightening at the end of the race.

Or maybe Election Graphs and RCP were just lucky in 2016. That might also be the case. This is VERY POSSIBLE!

Anyway, that is the big story of the week.

But we still have to review the rest of the main charts! So here we go!

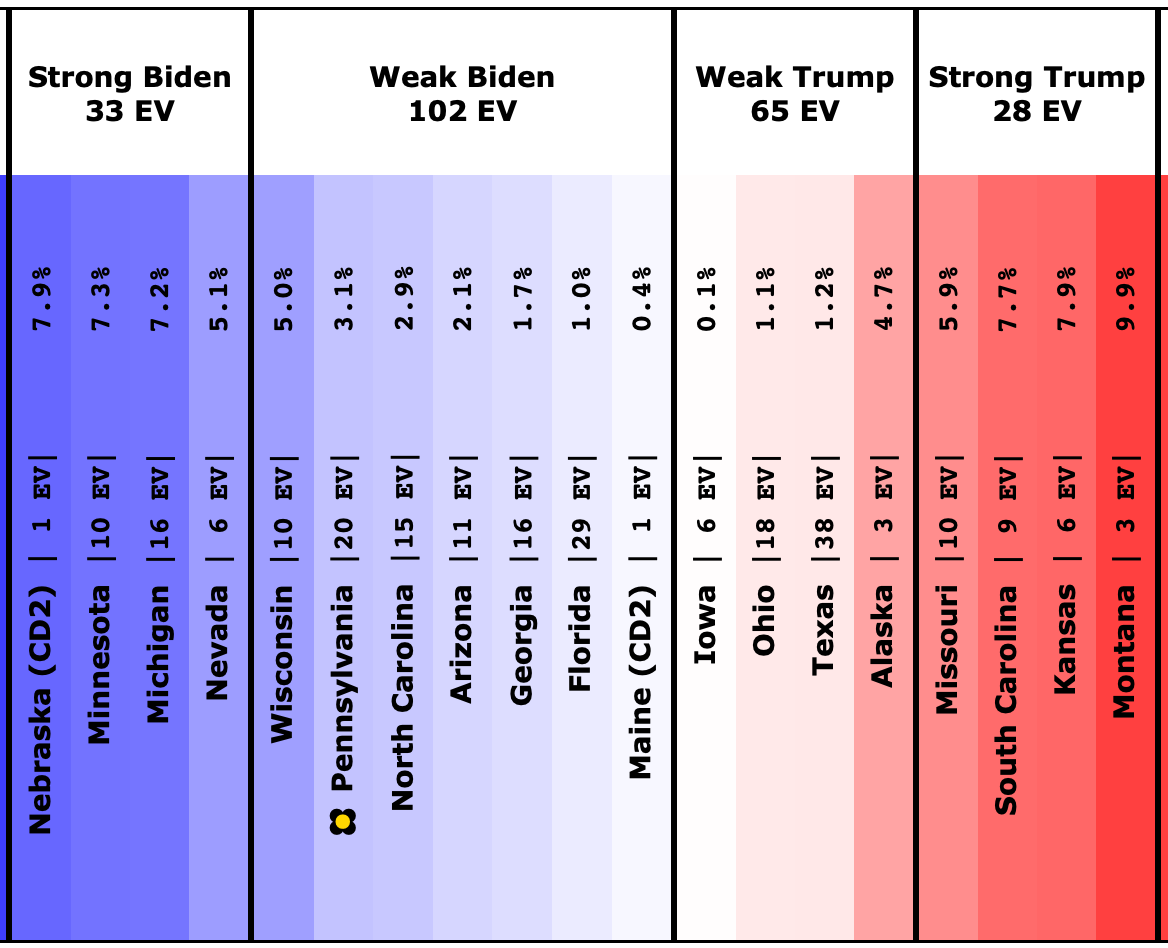

First up, states that moved in or out of our "Weak Biden" and "Weak Trump" categories:

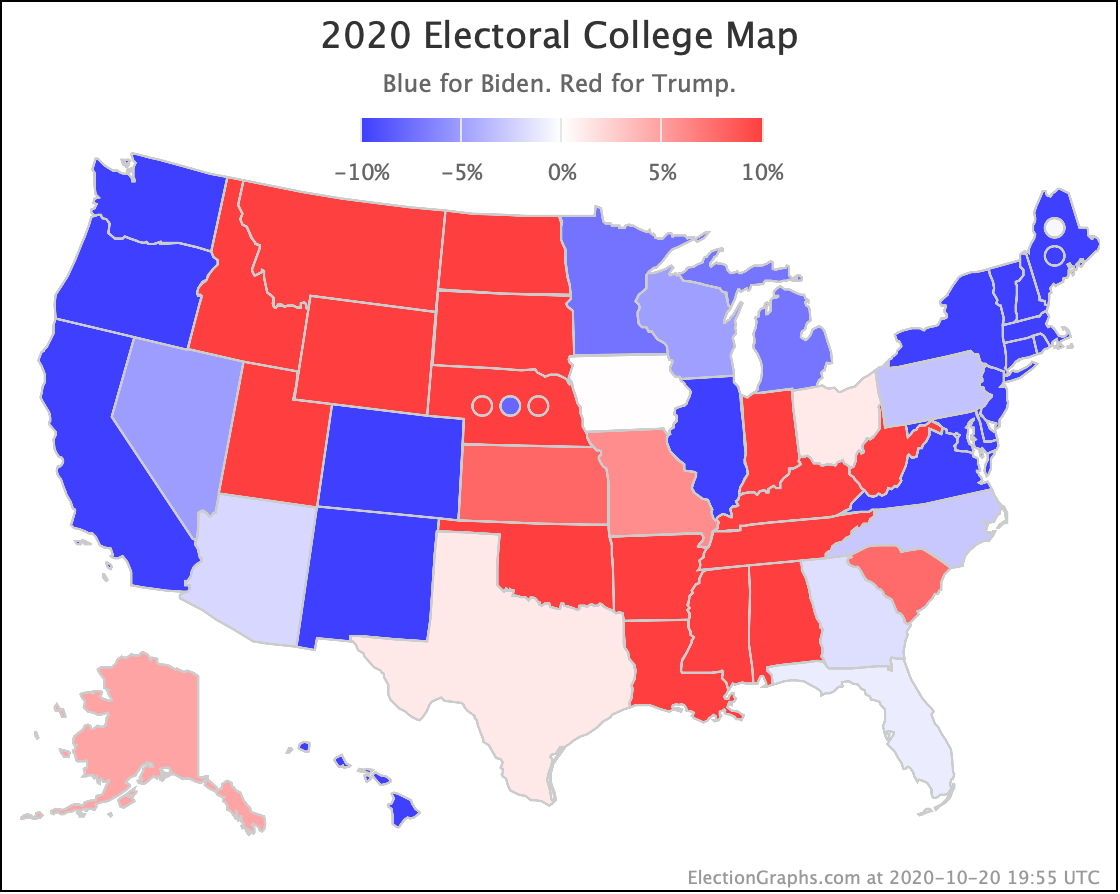

OK, we already talked about Pennsylvania, but here it is again. It moved from Strong Biden to Weak Biden since the last update, and as the current tipping point state drives a lot of the national picture too. But we discussed all that, so… moving on…

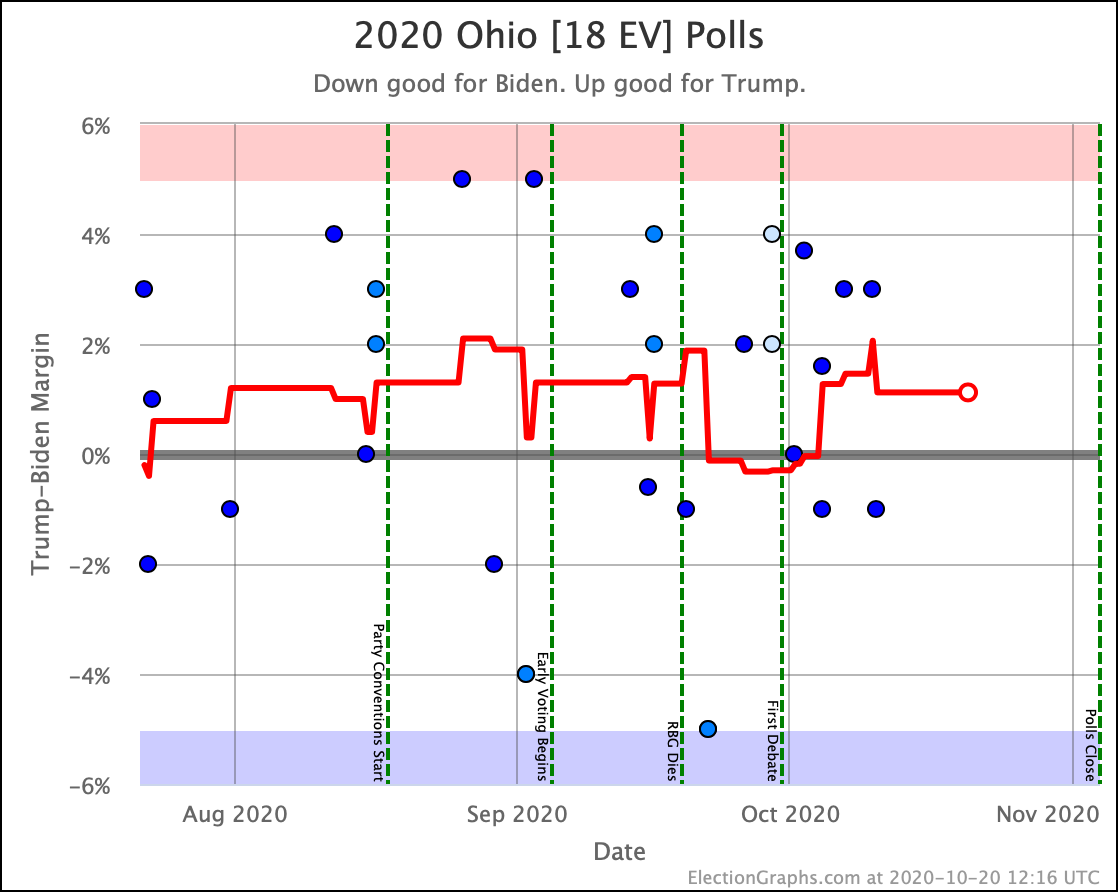

Last time Ohio had moved into the blue zone by the thinnest of margins. Now it returns to "Weak Trump" where it has usually been. Either way though, Ohio is extremely close.

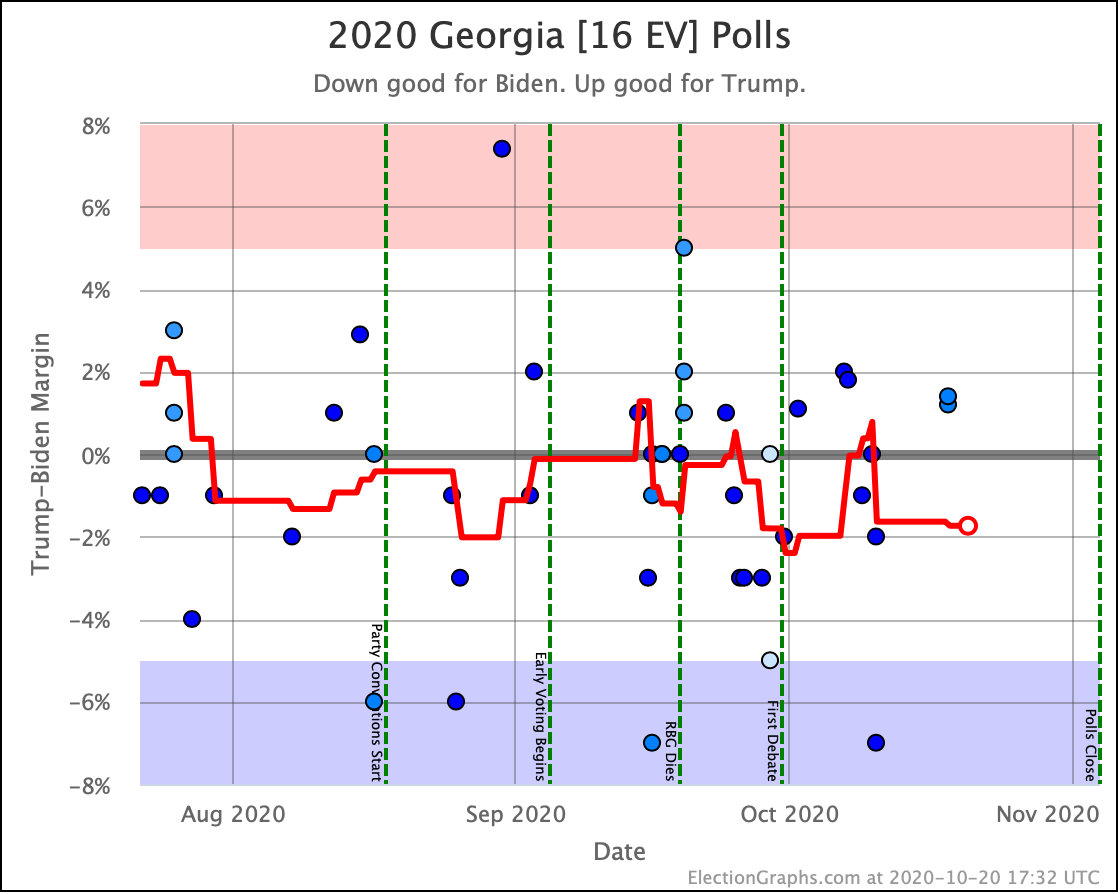

Since last time, Georgia popped over to the Trump side of the centerline, but it didn't last long, and Georgia is back to being just barely blue. Just like Ohio though, the truth is that Georgia is extremely close and could easily go either way.

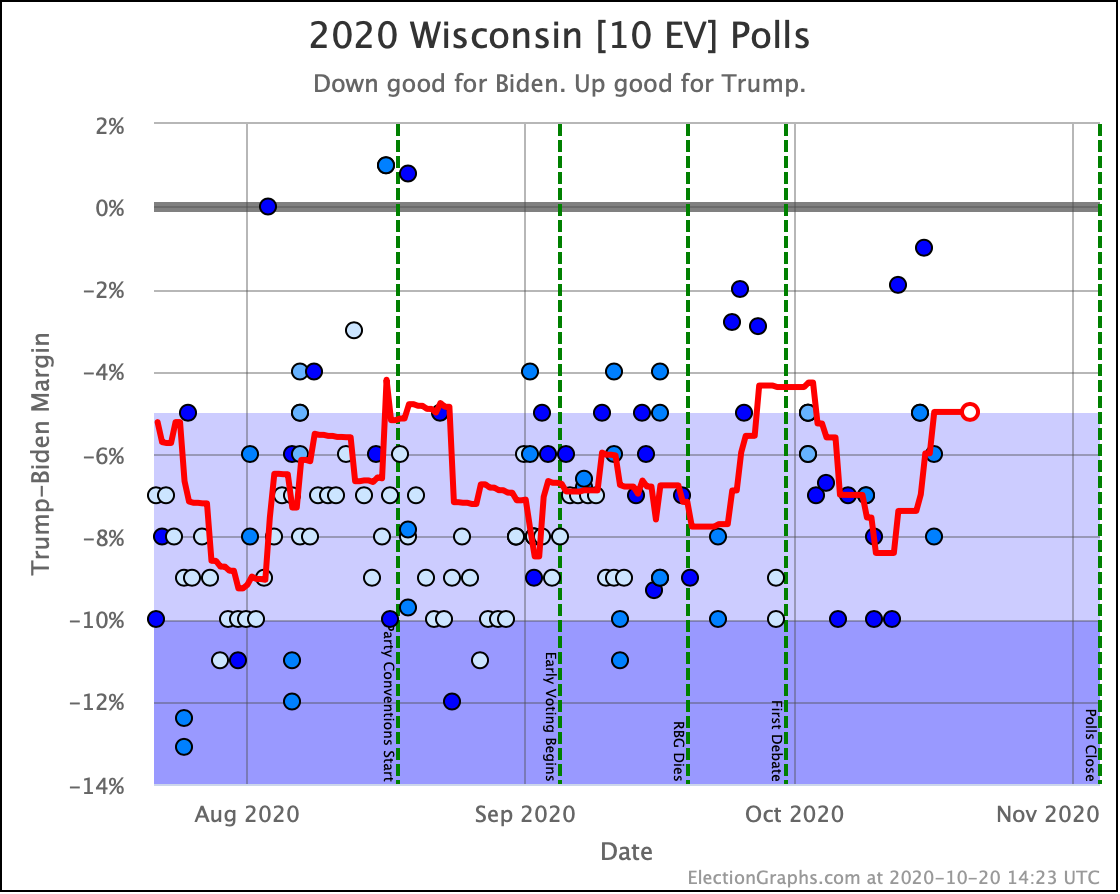

Since the last update, there has been significant weakening in Wisconsin, with it just barely moving into the "Weak Biden" category with the last poll. But if you look at the specific polls in the Wisconsin average, you see EXACTLY the same sort of issues we discussed with Pennsylvania.

If the tightening in Pennsylvania turns out to be a mirage based on having a bunch of low-quality pollsters releasing results recently, then most likely it will also be a mirage in Wisconsin. If Pennsylvania turns out to be real on the other hand, then Wisconsin probably will be too. (Thus showing why assuming completely independent states is not realistic, and we need to balance that by also showing uniform swing.)

But like Pennsylvania, if I had to bet right now, I'd say that Wisconsin has been in a 4% to 8% range for most of the last few months, and we are just at the low end of that range for Biden right now, and we'll probably revert back to the middle of that range with a few more polls.

But we won't really know until we indeed get a few more polls.

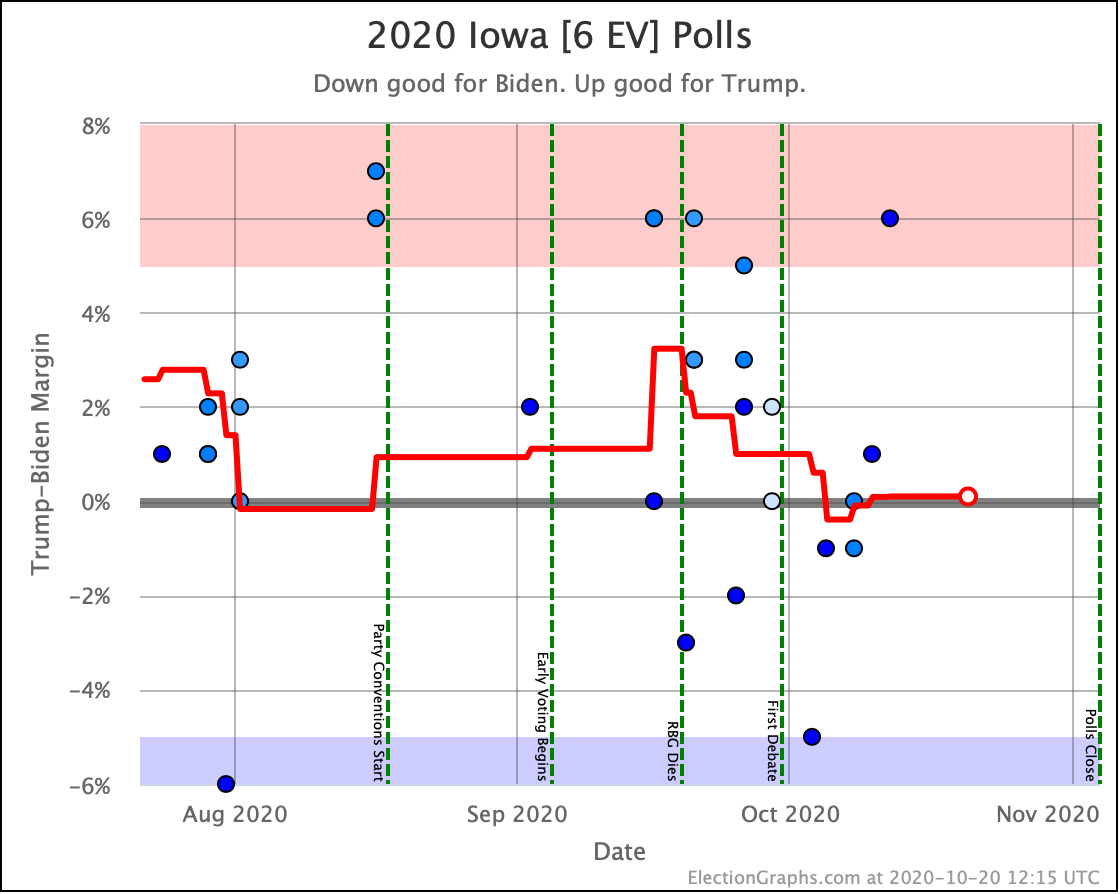

Like Ohio, last time Iowa had popped over to the blue side of the line, but this time it reverts to being just barely on the red side like it usually has been. But like Ohio and Georgia, the bottom line is Iowa is too close to call.

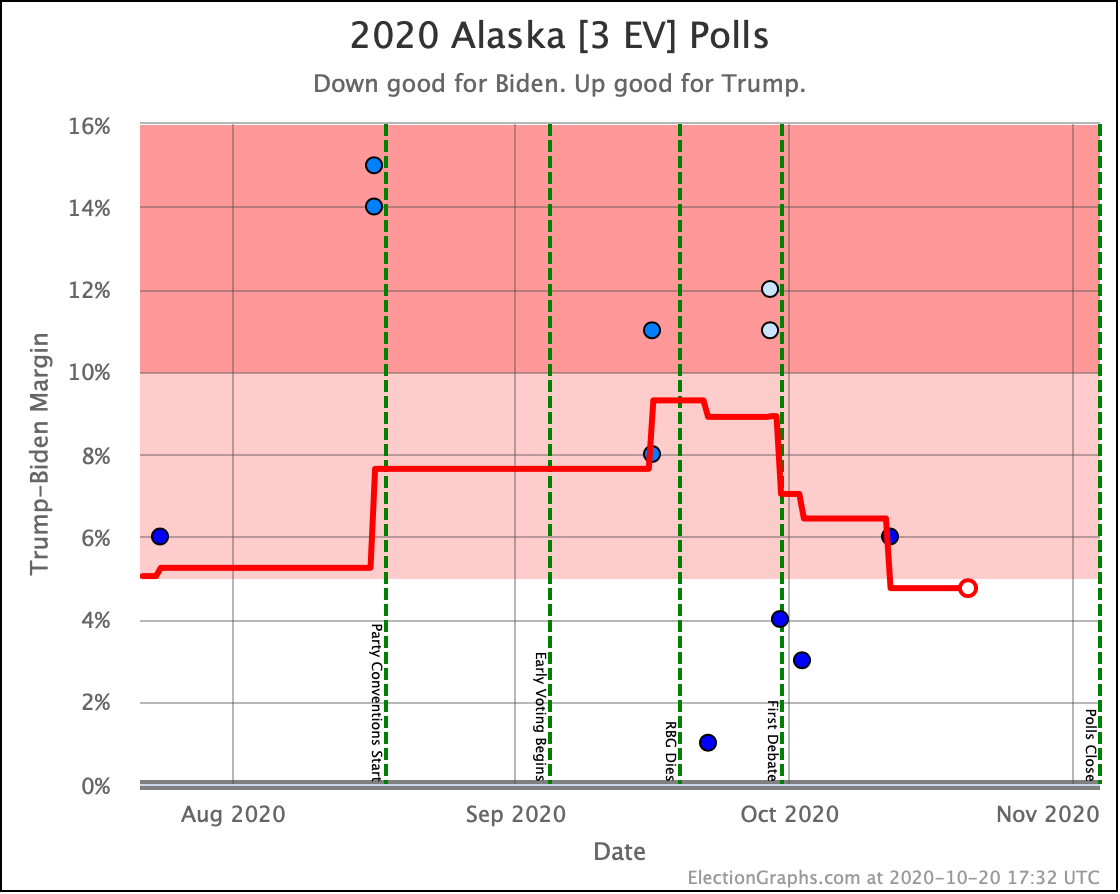

And finally, Trump's lead drops below 5% in Alaska, bringing it into range as a possible pickup in a Biden landslide scenario.

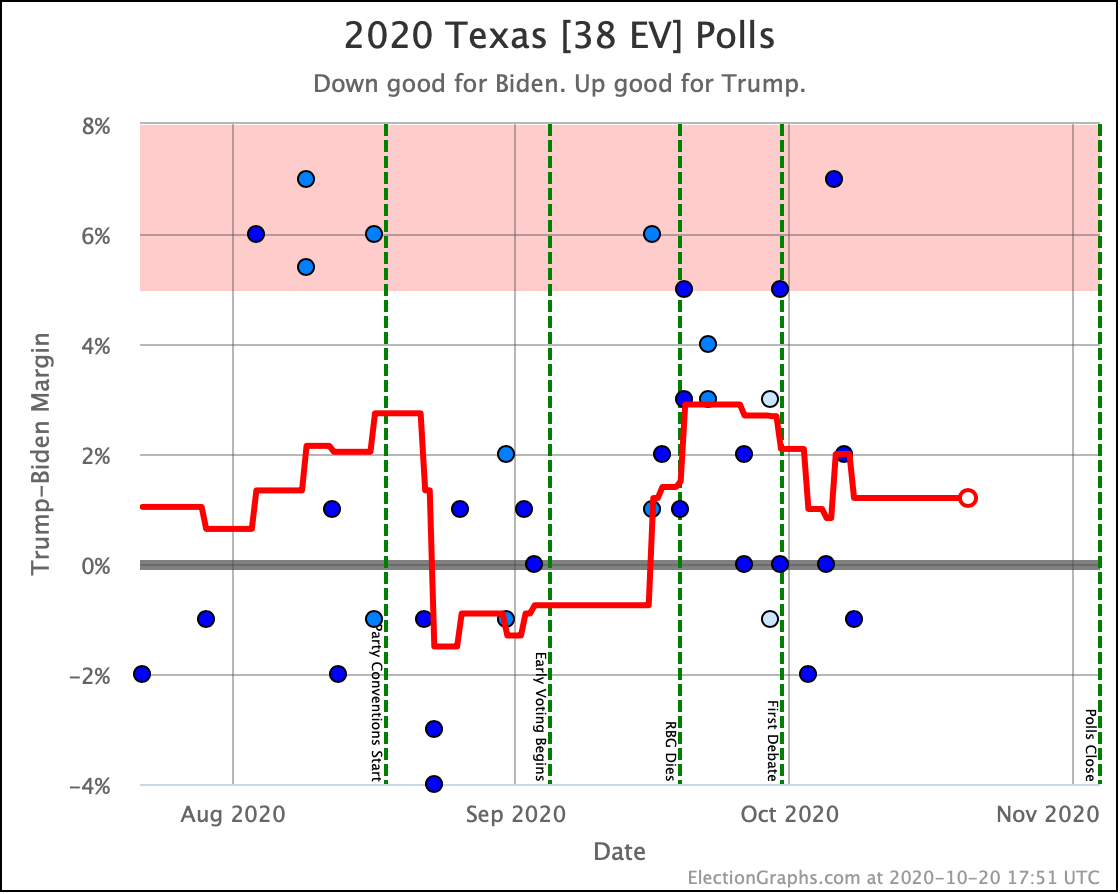

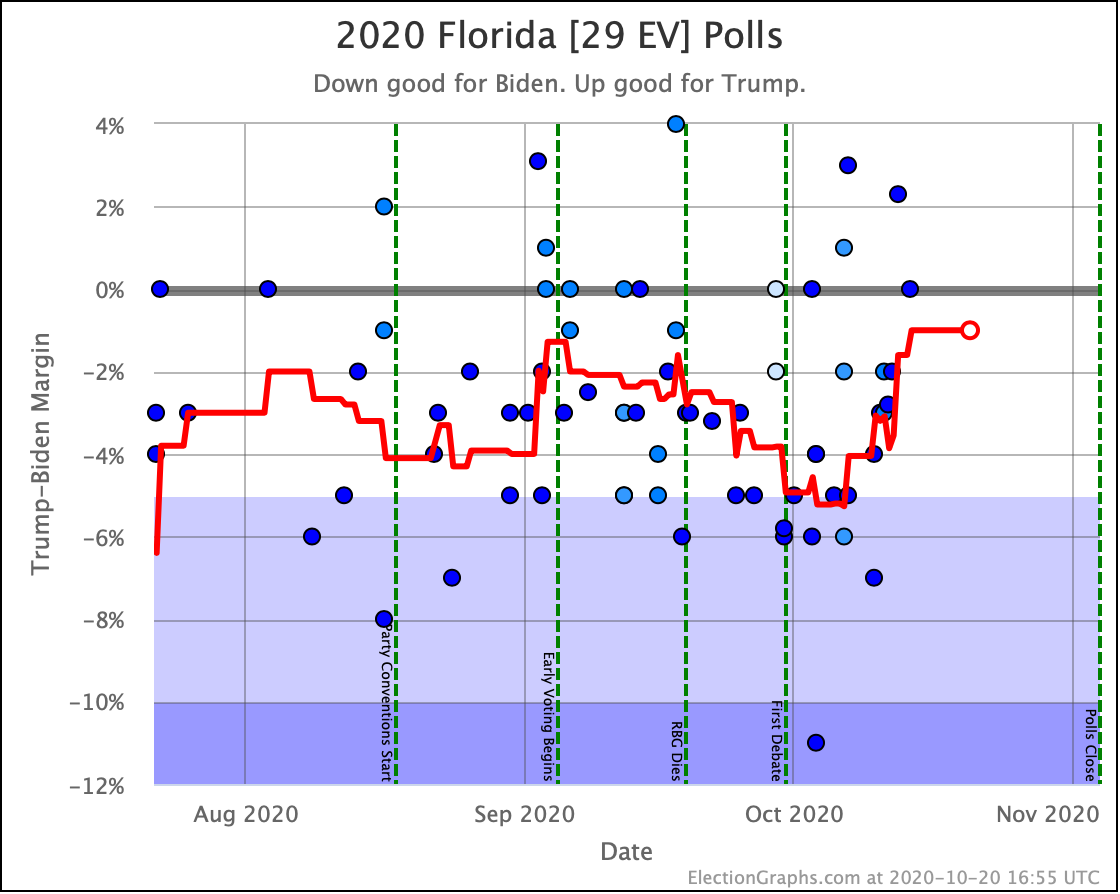

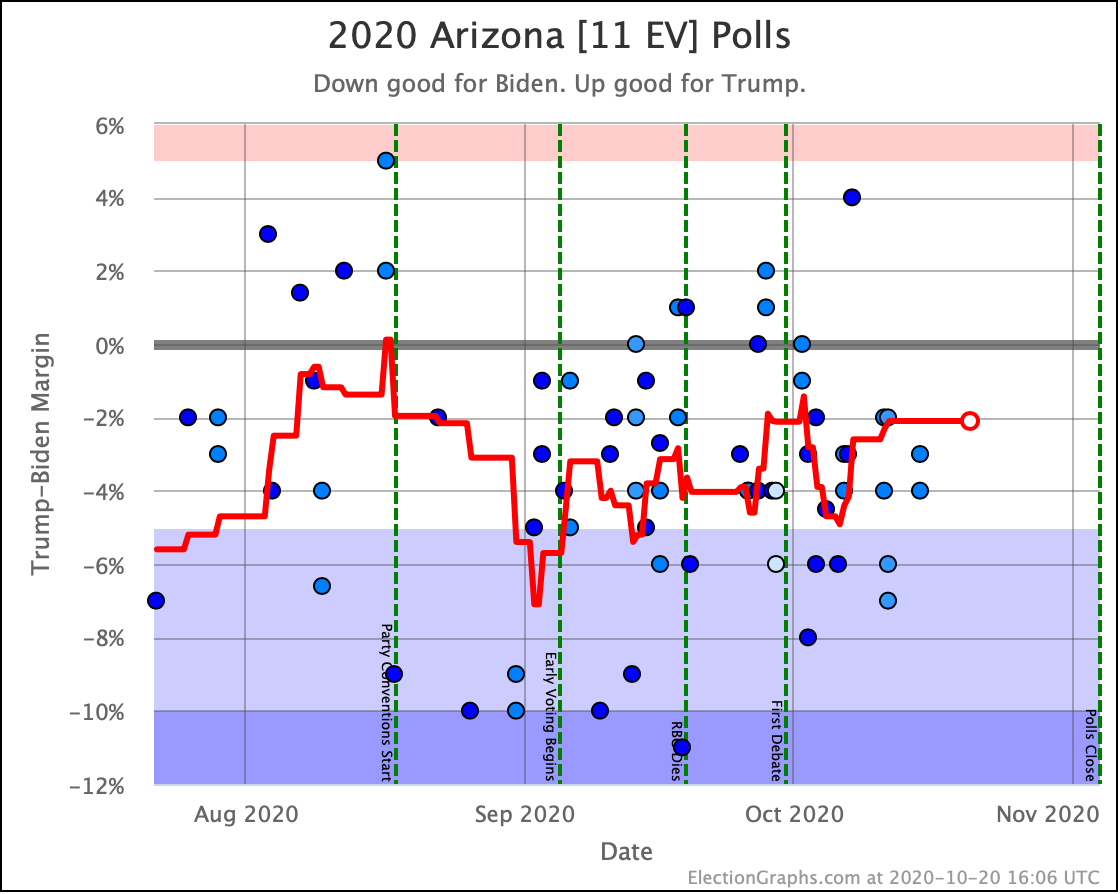

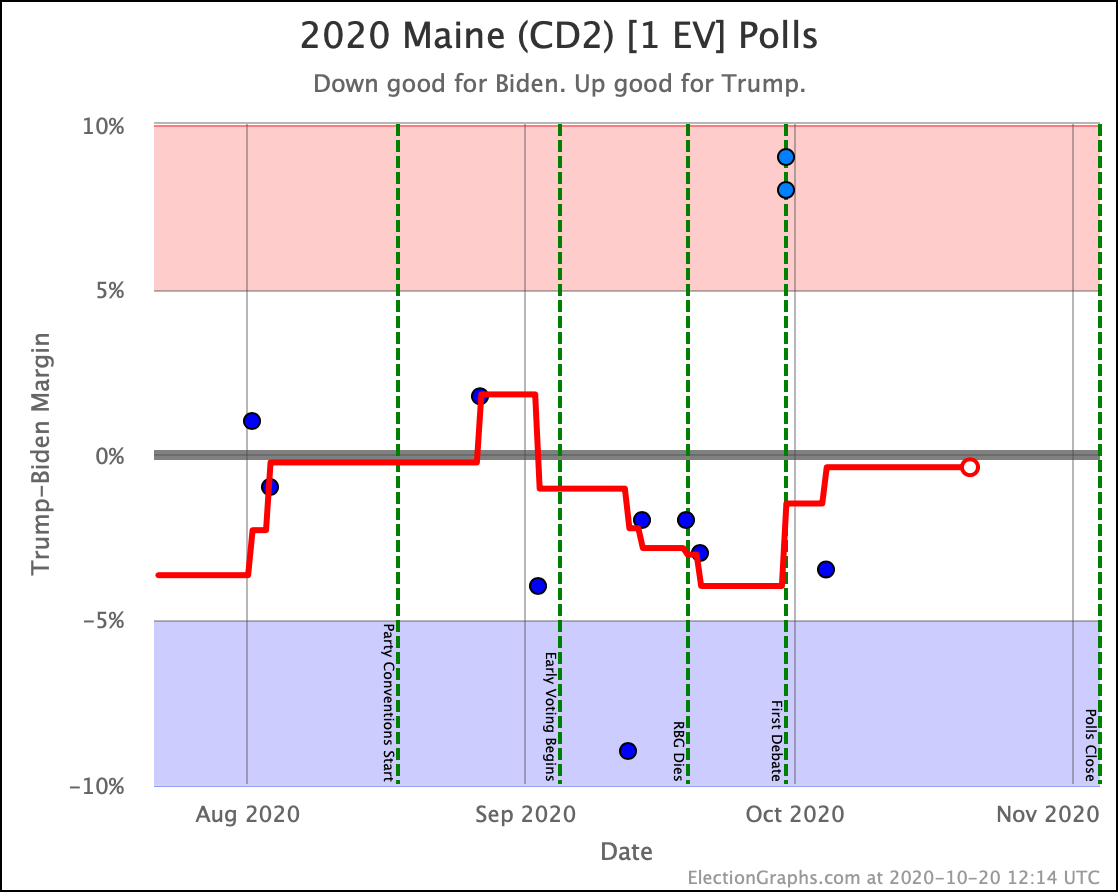

OK, now the rest of the close electoral votes we haven't already discussed, without additional commentary:

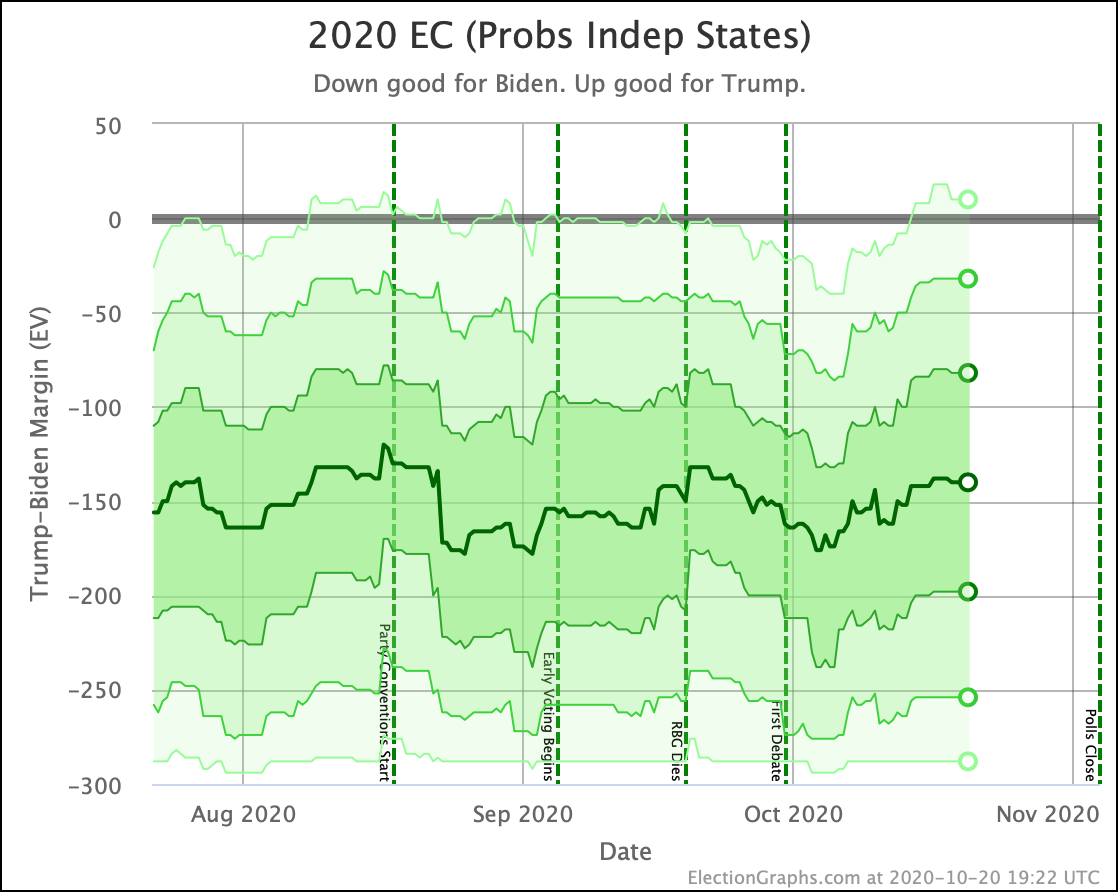

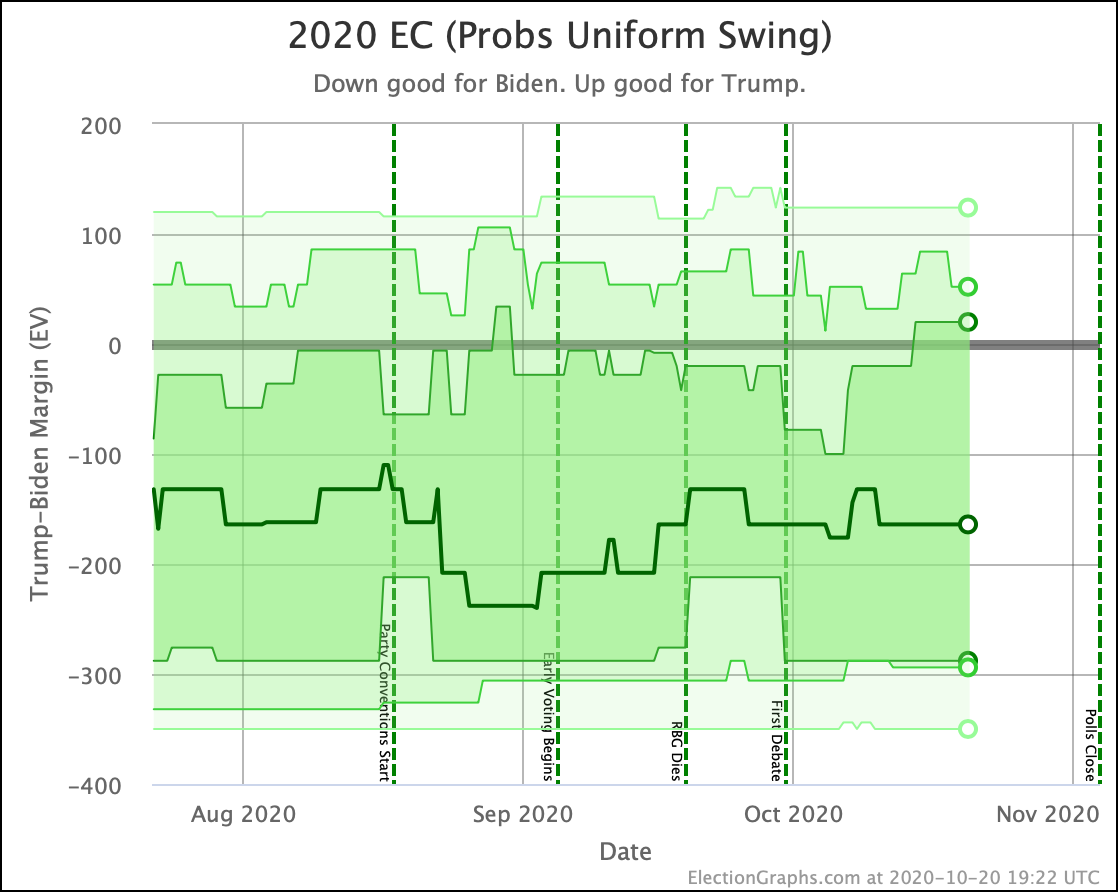

OK. With those out of the way, let's look at our three "envelopes" with the ranges of possibility in the categorization view, and the two extreme probabilistic views:

Unlike the tipping point, where it looks like a breakout from the normal "since June" range, all three of these views show us basically consistent with where this race has been since July.

In all three cases, Trump's high end does look a bit better than it did a few weeks ago and is near the high end of Trump's range. And in all three the centerline is closer to the worst of Biden's range. But none of these are breaking out from the normal range.

Right now that "breakout" is only showing up in the tipping point. Which means that while the range of possible options is about the same, it is more precarious, because Biden's lead in the tipping point state is a lot less than it had been.

Subject again to all the caveats we discussed earlier in the post of course. I won't repeat them here.

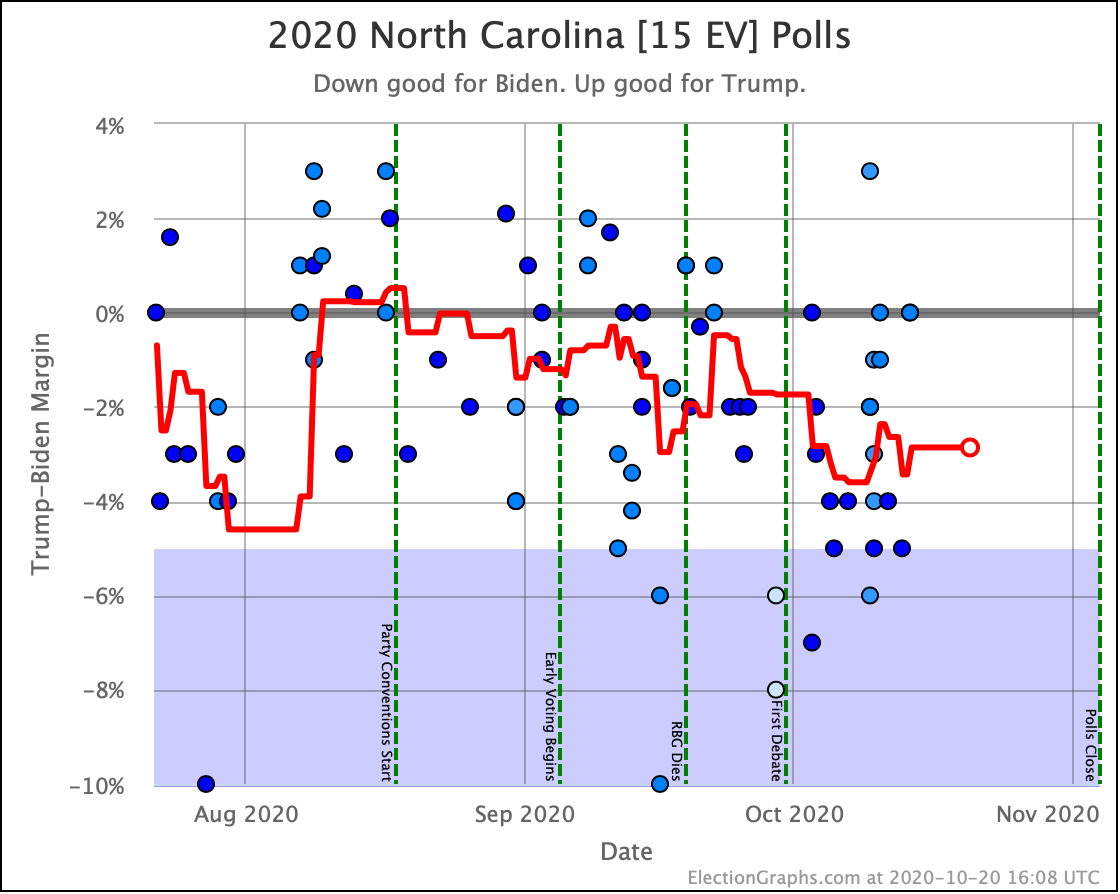

Bottom line, carefully watch the next polls in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina… the three states currently closest to the tipping point… to see if the tipping point reverses itself right away, or if it starts to look like the new closer tipping point might be real and sustained.

In the meantime, here is the current spectrum of states where the margin in the averages are under 10%:

The RCP average of national polls currently shows an 8.6% Biden lead. Comparing to the 3.1% tipping point, this implies that the structure of the electoral college is currently giving Trump a 5.5% head start… if this tipping point holds up. This "head start" is up from 3.4% in the last update.

The increase in this head start is due to the margin in the tipping point of Pennsylvania dropping considerably while the national margin, while it has tightened a bit, does not show the same kind of movement. Which again, is one reason to suspect maybe the Pennsylvania movement will prove to be an illusion. More polls will resolve that question soon enough.

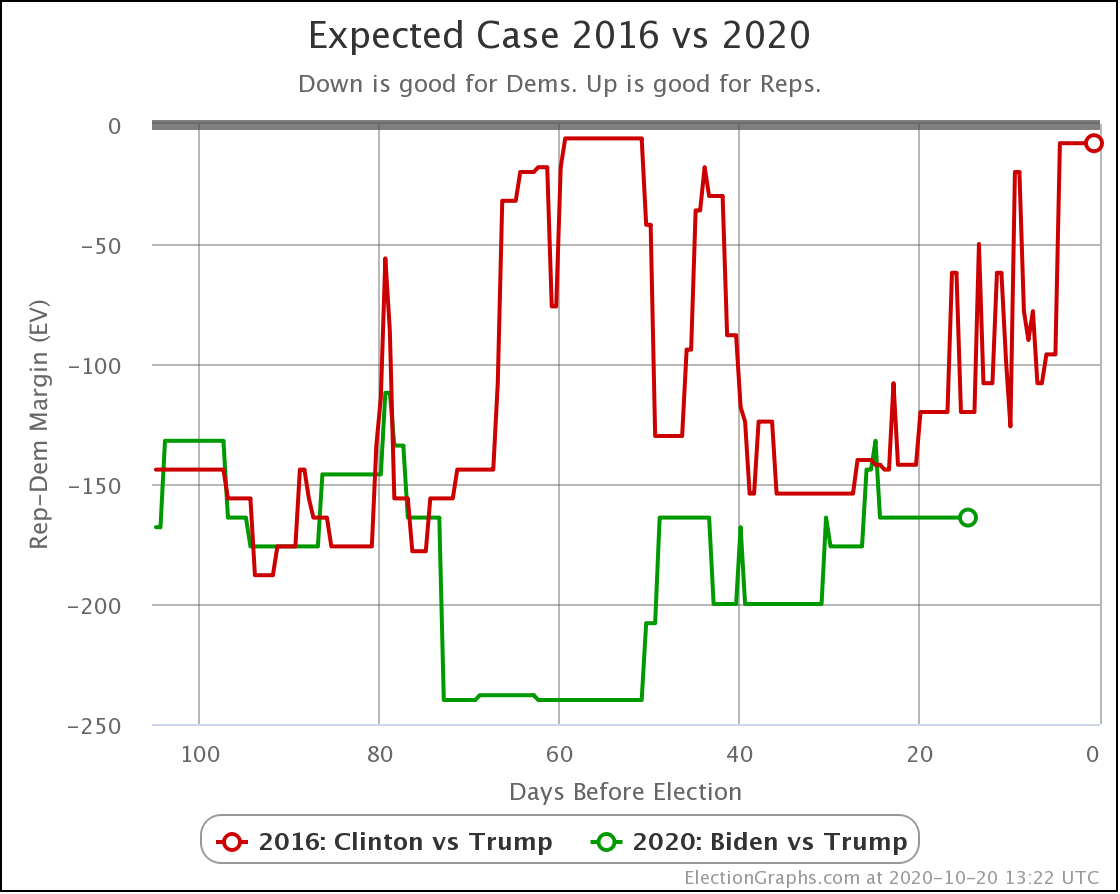

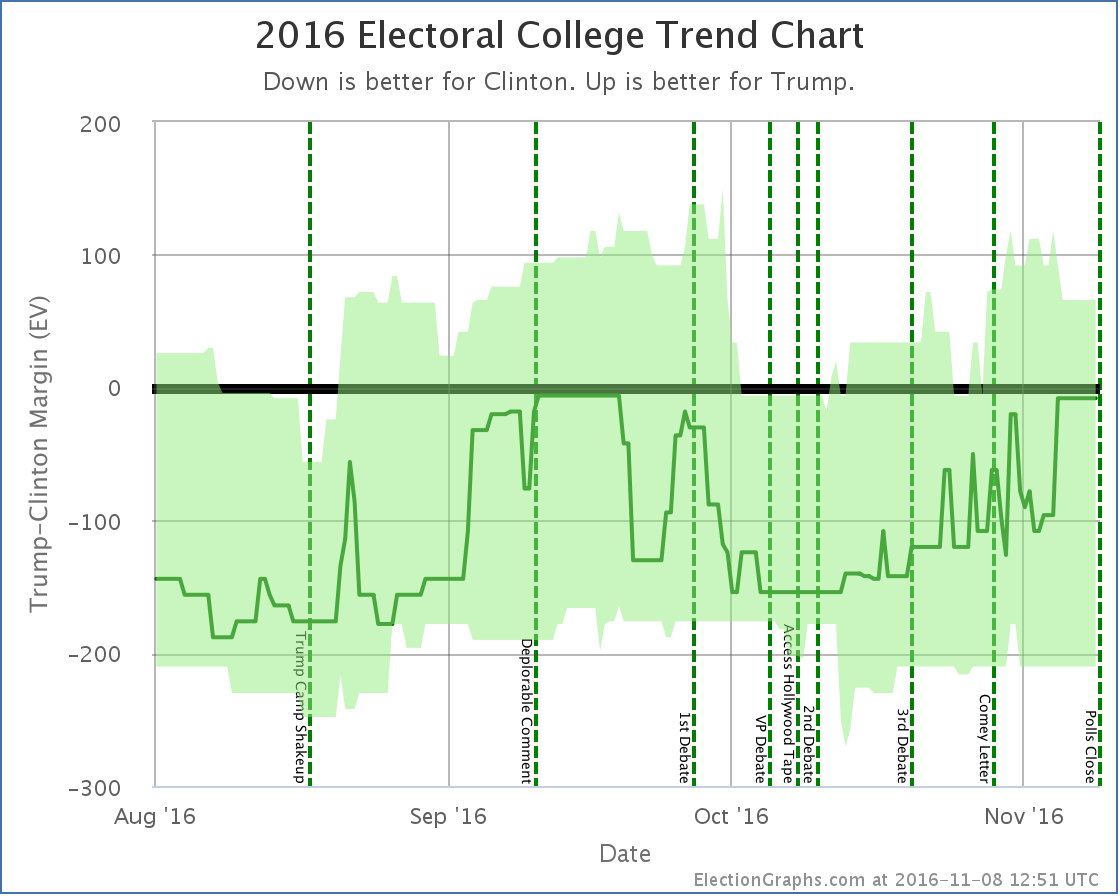

Finally, time for the 2016 comparison:

In the expected case, where each candidate wins every state where they lead the average, Biden continues to outperform Clinton at the same point in time four years ago, although not by as much as he was a month ago, and there was a short moment where he moved above her curve. But for the most part, Biden has been outpacing Clinton on this metric.

Meanwhile, the same can't be said at the moment for the tipping point.

While the general trend of Clinton weakening started at about the 30-day point, at about this moment, two weeks out, Clinton had a bunch of good polling and had one final peak before her final collapse. Meanwhile, as we have discussed, Biden's tipping point is now the smallest it has been since June 10th.

If this is just an aberration, and it gets reversed or erased by new high-quality polls that come out in the next few days, then the picture will be back to what it has been for months. Namely, Biden is heavily favored, but a Trump win is not impossible.

If however new polls sustain this change, then it would indicate that Trump's chances of winning have increased substantially, and there is a real race happening in these last two weeks.

Watch the next few days of polling, and we should know which scenario we are in.

Right now, with our current averages, and the two extreme probabilistic scenarios, Election Graphs gives Trump's odds of winning as somewhere between 0.3% and 23.3% depending on how correlated the polling errors in each state end up being.

That's a big range of course, and that is "if the election was today" when we have two weeks left. But at the very least, it means to take the chances of a Trump comeback and win seriously.

We shall see.

Finally, the map as it stands right now:

I locked the poll updates on Monday evening US time to make this update. As I finish writing the post it is now Tuesday afternoon. As usual for this point in the cycle, there have already been a bunch of new polls released during that time. So I'll be getting back to data entry shortly.

I've taken the remaining time from now until the election off from the day job to better be able to keep up with the deluge of new polls. That also probably means you'll get more than just one update here on the blog before election day.

So keep checking in for updates, both here on the blog and on the main 2020 Electoral College page.

But first, the usual closing with the countdown:

14.1 days until the first results start coming in for Election 2020.

We are in the home stretch. Almost there now!

For more information:

This post is an update based on the data on the Election Graphs Electoral College 2020 page. Election Graphs tracks a poll-based estimate of the Electoral College. The charts, graphs, and maps in the post above are all as of the time of this post. Click through on any image for current interactive versions of the chart, along with additional details.

Follow @ElectionGraphs on Twitter or Election Graphs on Facebook to see announcements of updates. For those interested in individual poll updates, follow @ElecCollPolls on Twitter for all the polls as I add them. If you find the information in these posts informative or useful, please consider visiting the donation page.